“What we do is determined by who we are.”

It’s a given that individuals act “according to their nature” – i.e., “what we do is determined by who we are.” But how do we analyze our nature, and how do we apply that insight to the business environment? Self-awareness is critical to understanding the range of actions we’re willing to undertake, because, as a general rule, no matter how others advise us, we are not going to act in a way that is contrary to our nature.

There are numerous personality assessment methods, all with their individual merits. However, for our purposes here, I want to simplify the discussion of “nature” by going back to Nature itself. I can think of no better analogy for business & financial survival strategies than the primitive reality we all face every day:

“It’s a jungle out there.”

Since time immemorial, our environment has always offered a mixture of threat and opportunity. And the oldest law of survival still applies:

“Try to eat without being eaten.”

Simply put, Nature has evolved two basic methods for self-preservation, and humans developed a third. These basic survival strategies can be divided into three groups: Grazers, Growers and Hunters. These groupings not only characterize species and societies, they also describe business and financial tendencies. So let’s explore this “business animal kingdom” to see where we fit in.

Grazers (or, “What’s Gnu with you?”)

Grazers generally rely on serendipity (“Here’s a nice patch of grass!”) and memory of what worked in the past. (“There was always grass there before.”) And of course there’s a preference for “low-lying fruit.” They tend to be “set in their ways,” repeating established patterns. (Migrations follow the same route over and over again.) They also tend to be herd animals, seeking safety in numbers, hence the term “herd mentality.” And there’s nothing wrong with a herd mentality, if the herd is successful. (Oldest rule in the stock market: “Don’t fight the tape.”)

Many businesses embody Grazer philosophy: they tend to do the same thing over and over again, because it always worked in the past. Over and over again, they sell the same product and services to the same customer groups (“familiar pastures.”) They run the same “sales” and offer periodic “specials” as they always have. You can think of numerous examples if you try – brick & mortar retail, convenience stores, even doctors, attorneys, and accountants. (Old CPA joke: “Why did the chicken cross the road?” “Because that’s what he did last year.”) Innovation is generally frowned upon, because change brings risk. True, the food usually comes to these Grazers rather than them going to the food, but the mindset and the end result is the same:

“If it works, don’t fix it.”

However, problems arise when the environment changes. If there’s a drought, and the forage dries up, what’s a gnu to do? What if the river is too swollen with rain to cross? What if another herd gets to the green grass before you do? (What if someone invents the internet, smart phones, social media, or virtual reality?)

When the predictable world of the Grazer is disrupted, survival is imperiled. The primary risk to the Grazer is change, and the Grazer has to be prepared to seek new pastures when and if change comes. But this is extraordinarily difficult to accomplish, because change is not in the Grazer’s nature.

Growers (“Old MacDonald had a farm…”)

Somewhere in distant prehistory, someone invented innovation. It started with a better hand-axe or spear point, but soon thereafter people figured out that instead of searching for low-hanging fruit, they could grow their own fruit! Agriculture was born, and with it, the foundation for modern civilization and specialization. Freed from the nomadic imperative of both hunters and gatherers, it was possible for the first time to consistently stay in one place. (To this very day, we call that “putting down roots.”)

Agricultural success depends upon how much produce Growers can generate from the limited amount of land available to cultivate. Complicating the goal of yield maximization are the numerous threats they face from weather, infestation and predation. The rainfall they depend on may be too much, too little, or at the wrong time. Crops may be blighted by disease or consumed by swarms of insects and birds. Growers face a myriad of natural risks, and thus must devote as much effort to risk mitigation as to yield maximization.

Growers are both risk minimizers and careful innovators.

Like Grazers, Growers also depend upon recurring cycles. Unlike Grazers, Growers engage in considerable planning to minimize cyclical risks. In order to prosper, they must, by nature, be adaptable.

To increase yield per acre, they look to improved crop varieties – higher yield, more disease and drought resistance – and better planting methods. (Farmers invented the “pilot project” – “Okay, we’ll try it over in that corner and see how it does.”) Irrigation has been used for millennia to mitigate insufficient rainfall. But modern agriculture isn’t “Little House on the Prairie.” It’s using satellite imagery and topological maps, to plot multiple crop plantings to maximize water utilization and harvesting efficiency. Still, all that innovation is grounded in caution and age-old wisdom: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

“Old MacDonald” had a balanced portfolio.

Remember the children’s song? Old MacDonald didn’t just plant crops. He raised livestock too –cattle, ducks, horses, chickens, sheep, etc. Old MacDonald further minimized his risk by increased diversification. He was a visionary. He didn’t just have a farm: he founded MacDonald Amalgamated Diversified Industries, Inc.! (Stock symbol EIEIO...)

Manufacturing-and-production-based businesses are a natural outgrowth of the agricultural model. Demand may be cyclical, as in lawn equipment, swimwear and snow shovels. Efficiency is vital to success, as is minimizing risk. Production planning requires forecasting future events and market conditions, along with labor, equipment & capital requirements. In addition to market risks, these businesses face the possibilities of supply-chain disruption, labor problems, cost escalations, etc. Product diversification is needed to minimize the risk of reduced market demand and product obsolescence. Diversification includes finding new uses (markets) for existing products (“Hey, if we put a handle on surgical tubing, we now have exercise equipment!”)

In short, Growers tend to focus on planning, resource optimization, and risk management.

Their greatest threats come from unexpected external forces and mismanagement of internal resources. And the latter is often underestimated. The larger & more complex the Grower’s enterprise, the more “moving parts” there are to manage, and the greater the risk that a problem in one area may snowball throughout the whole organization. And as with agricultural endeavors, bad decisions often have long life cycles. The Grower’s challenge is to control what he can, hedge against what he can’t, and be ever vigilant on both.

Hunters (“If you want to eat, you’re going to have to kill something.”)

Hunters face the same challenges as Grazers:

“No Gnus is not Good News.”

Hunting is the natural complement to grazing. The lines were early drawn between predator & prey, but those lines are relative: big fish eat little fish, and are in turn eaten by bigger fish. There is always the possibility that the hunter may become the hunted.

Hunting is often a group endeavor, requiring coordination and cooperation with others. Hunters by definition are risk-takers. They follow wherever perceived opportunity leads them, often venturing far afield in search of their quarry. While they are certainly guided by experience (“the deer will come to the stream to drink”), they must also be acutely in tune with their current environment (“you have to be downwind or they’ll pick up your scent.”) They have to be able to “read the signs.” If there is no spoor where they are – tracks, scent markings, scat, etc. – then they must search elsewhere. And sometimes there is simply no game to be found. Maritime hunters face the same challenges as their land-based counterparts:

There’s a reason it’s called “fishing” instead of “catching.”

Even when game is found, there is often risk involved in the kill. (Famous aviator’s adage: “There are old pilots, and bold pilots, but there are no old bold pilots.”) The balance between discipline and daring is fluid, but it must be maintained. Hunters tend to skew the risk/reward analysis toward the potential reward: “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.”

It can be argued that every salesperson is a hunter, but the general business model for a Hunter is entrepreneur or start-up. The primary characteristic is risk-taking. (Not every start-up conforms to the Hunter/ risk-taker model – there’s a big difference between starting a company that’s just like other companies vs. trying to create a revolutionary product or service. Opening a new McDonalds is not the same as creating SpaceX.) Hunters have a “moonshot mentality.”

A Hunter has to look ahead while watching his back.

The Hunters’ risk is primarily twofold: first, that the hunt may not be successful – the game may not be found, or worse, the quarry may escape and the effort wasted – and second, that the hunter may be injured or killed in the process.

In business, the target market may not be there at all, or it may not be successfully captured. Worse, there may be such injury to the company – depletion of capital and other resources – that the enterprise may not survive. In Hunting Groups, the group may lose confidence in their leadership. (In predator groups, the “Alpha Male” always faces the risk of rebellion or challenge for supremacy.) Or the group may become dysfunctional due to internal strife.

The Hunter’s primary challenge is to maintain focus on the objective, to avoid distractions, and to avoid injury in the process.

So which one are you?

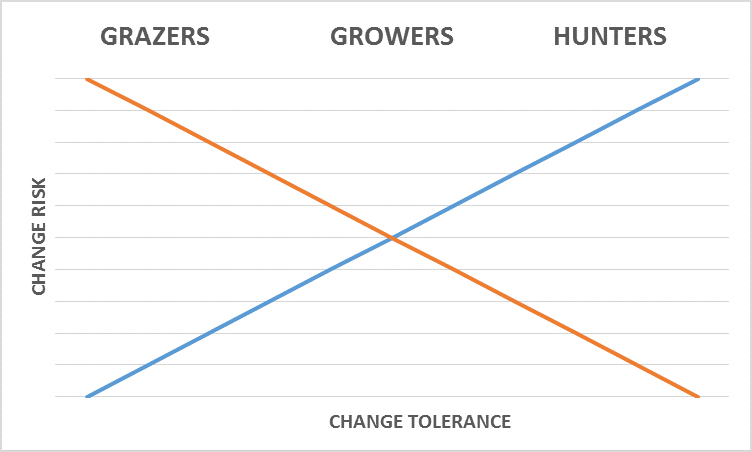

The following chart summarizes the primary differences among these groups in terms of change tolerance and change risk:

As illustrated above, those most at risk from changes in the business environment are also those least inclined to risk changing how they do things. The Grazer’s natural tendency is to resist change, and when forced to change, to adopt the least amount of change that is absolutely necessary. The Grower sees change as a necessity to mitigate risk, a risk/reward balancing act that requires careful planning. The Hunter embraces risk – change is just another part of his environment.

It should be emphasized that the categorization of Grazer, Grower or Hunter is not primarily dependent on the business type (manufacturing, retail, technology, etc.) The examples above are just examples. The distinction is determined by the nature of the business owner(s) and management. In every business segment, there are firms that are Grazers, Growers and Hunters.

For each of these three groups, business and financial decisions will made in the context of their basic nature. It is unrealistic to expect otherwise. Any endeavor requires whole-hearted commitment to succeed, and pursuing a course contrary to our nature will be half-hearted at best. In sum, we all will act according to our nature unless forced to do otherwise. The better we know ourselves (our nature), the better able we will be to choose – and stick to – acceptable options and strategies. There are successful Grazers, Growers & Hunters everywhere. They know who they are, and act accordingly. So which one are you?

Copyright 2016 Donald R. Pinkleton. All rights reserved.